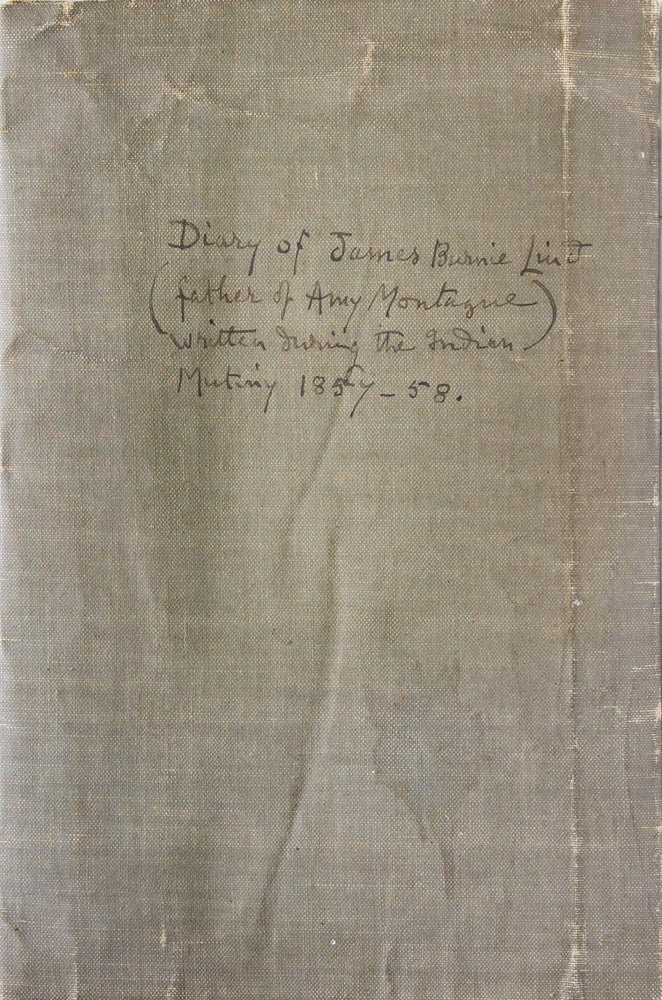

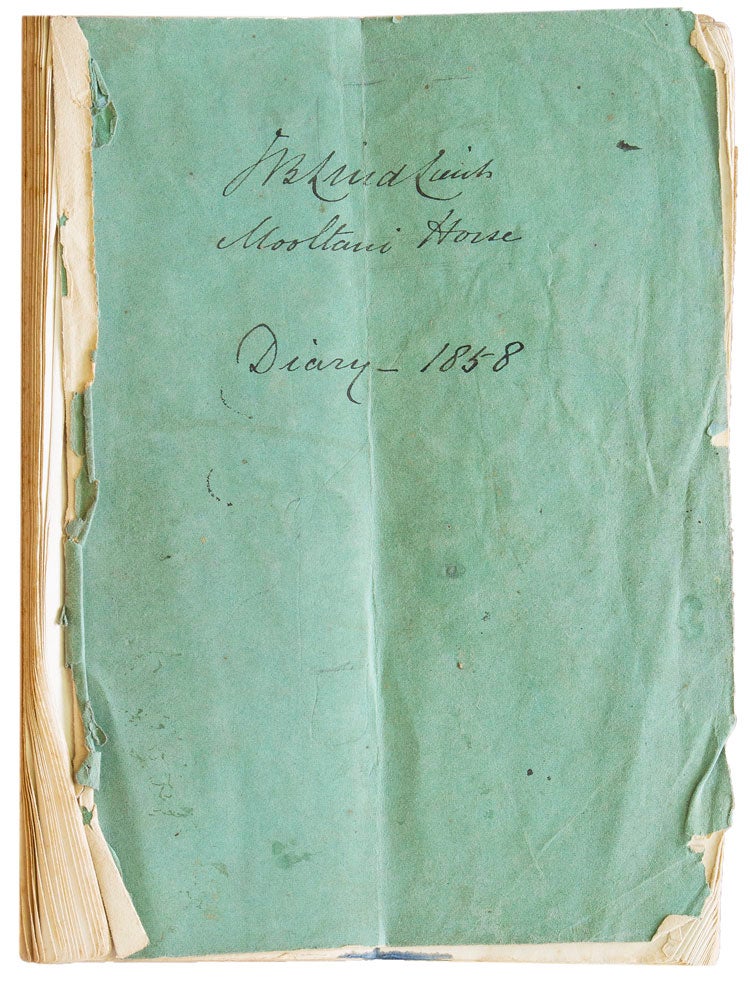

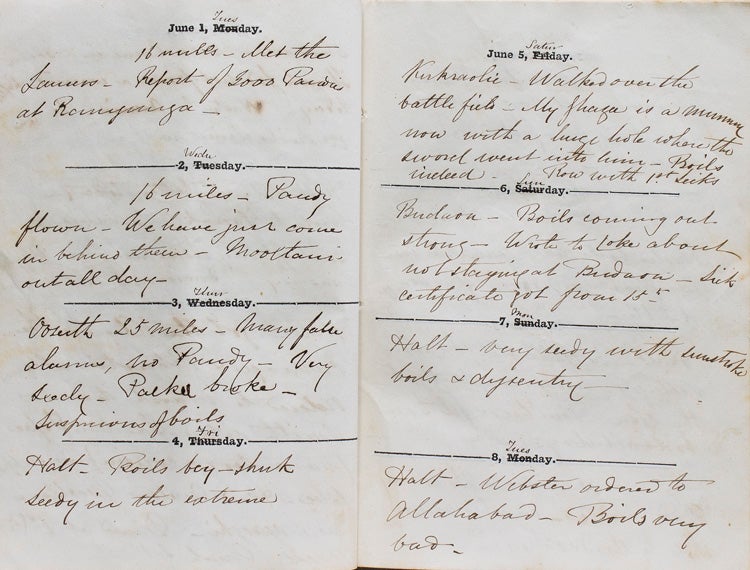

Original manuscript diary documenting the service of a British officer during the latter stages of the Sepoy Mutiny.

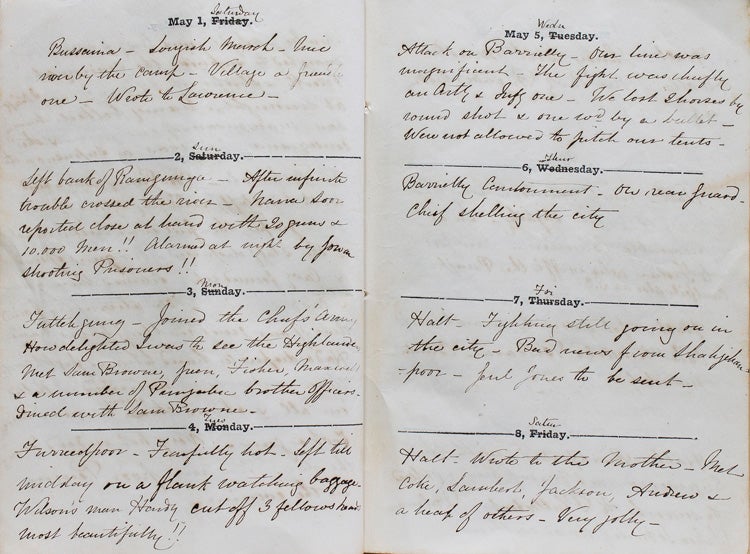

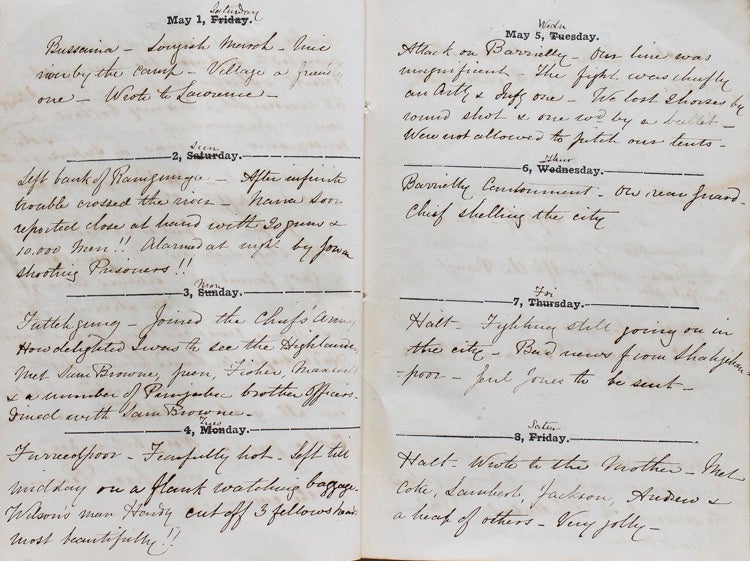

January-December 1858.

Price: $6,000.00

About the item

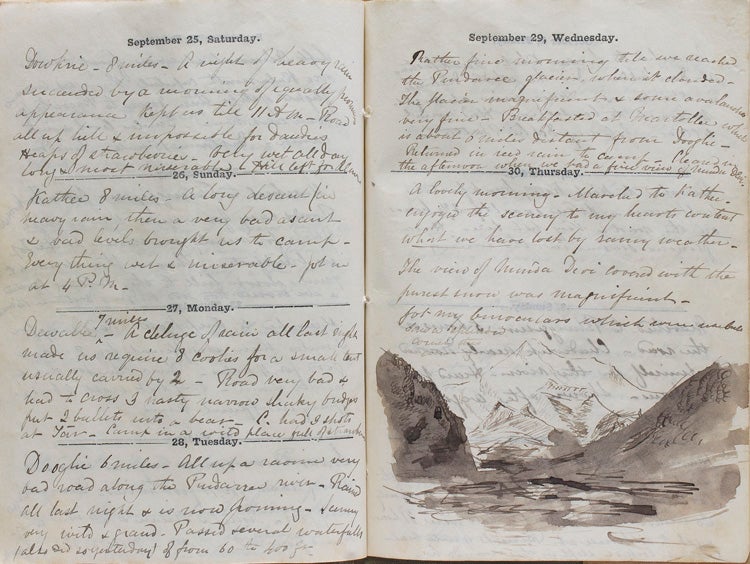

Contains 96 pages of entries composed in both ink and pencil. 8vo. Bound in original paper wraps. Contains 96 pages of entries composed in both ink and pencil. Wraps worn, spine perished, else very sound.

Item #314573

This diary was kept by Lt. Co. James Burnie, an East India Army Officer who served in the Mooltani Horse during the Sepoy Mutiny. It follows his movements throughout the Indian countryside as he and his column track down and face the mutineers. His troops march through Patiala, Newlee, Kiraoli, Furreedpoor, Barreilly, Nawabganj and Tilsee and Shahjahanpur. His entries contain descriptive observations upon the terrain, marches, war news and details regarding deadly encounters with Sepoy troops. During the campaign Burnie suffers terribly from dysentry and heat stroke. His column often has to hunt for its food while out in the field and at other times, after a victory, they are able to raid the overcome town for supplies. During the latter part of the diary he includes a ink and wash drawing of Mount Nanda Devi. A rare first hand account of this rebellion that ended the vice grip of power of the East India Company over India.

“The Indian Mutiny also called SEPOY MUTINY (1857-58), was a widespread but unsuccessful rebellion against British rule in India begun by Indian troops (sepoys) in the service of the British East India Company. It began in Meerut and then spread to Delhi, Agra, Cawnpore, and Lucknow.

The mutiny broke out in the Bengal army because it was only in the military sphere that Indians were organized. The pretext for revolt was the introduction of the new Enfield rifle; to load it the sepoys had to bite off the ends of lubricated cartridges. There appears to be some foundation for the sepoys’ belief that the grease used to lubricate the cartridges was a mixture of pigs’ and cows’ lard; thus, to have oral contact with it was an insult to both Muslims and Hindus. Late in April 1857, sepoy troopers at Meerut refused the cartridges; as punishment, they were given long prison terms, fettered, and put in jail. This punishment incensed their comrades, who rose on May 10, shot their British officers, and marched to Delhi, where there were no European troops. There the local sepoy garrison joined the Meerut men, and by nightfall the aged pensionary Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II had been nominally restored to power by a tumultuous soldiery.

The seizure of Delhi provided a focus and set the pattern for the whole mutiny, which then spread throughout northern India. With the exception of the Mughal emperor and his sons and Nana Sahib, the adopted son of the deposed Maratha peshwa, none of the important Indian princes joined the mutineers.

From the time of the mutineers’ seizure of Delhi, the British operations to suppress the mutiny were divided into three parts. First came the desperate struggles at Delhi, Cawnpore, and Lucknow during the summer; then the operations around Lucknow in the winter of 1857-58 directed by Sir Colin Campbell; and finally the ‘mopping up’ campaigns of Sir Hugh Rose in early 1858. Peace was officially declared on July 8, 1858. A grim feature of the mutiny was the ferocity that accompanied it. The mutineers commonly shot their British officers on rising and were responsible for massacres at Delhi, Cawnpore, and elsewhere. The murder of women and children enraged the British, but in fact some British officers began to take severe measures before they knew that any such murders had occurred. In the end the reprisals far outweighed the original excesses. Hundreds of sepoys were shot from cannons in a frenzy of British vengeance (though some British officers did protest the bloodshed).

The immediate result of the mutiny was a general housecleaning of the Indian administration. The East India Company was abolished in favor of the direct rule of India by the British government. In concrete terms this did not mean much, but it introduced a more personal note into the government and removed the unimaginative commercialism that had lingered in the Court of Directors. The financial crisis caused by the mutiny led to a reorganization of the Indian administration’s finances on a modern basis. The Indian army was also extensively reorganized.

Another significant result of the mutiny was the beginning of the policy of consultation with Indians. The Legislative Council of 1853 had contained only Europeans and had behaved arrogantly as if it had been a full-fledged parliament. It was widely felt that lack of communication with Indian opinion had helped to precipitate the crisis. Accordingly, the new council of 1861 was given an Indian-nominated element. The educational and public works programs, roads, railways, telegraphs, and irrigation continued with little interruption; in fact some were stimulated by the thought of their value for the transport of troops in a crisis. But insensitive, British-imposed social measures that affected Hindu society came to an abrupt end.

Finally, there was the effect of the mutiny on the people of India themselves. Traditional society had made its protest against the incoming alien influences, and it had failed; the princes and other natural leaders had either held aloof from the mutiny or had proved for the most part incompetent. From this time all serious hope of a revival of the past or an exclusion of the West diminished. The traditional structure of Indian society began to break down and was eventually superseded by a westernized class system, from which emerged a strong middle class with a heightened sense of Indian nationalism.”

Reference:

The Sepoy Mutiny in India 1857-1858.

https://www.onwar.com/aced/chrono/c1800s/yr50/findia1857.htm.